Solid epoxy resins are widely used in 3D printing for the production of various functional components. According to an article by science writer Reginald Davey—summarized by Nanjixiong—this paper focuses on the application of solid epoxy resins in additive manufacturing, as well as recent research on improving isotropy in these materials and developing structures with enhanced temperature- and strain-sensing capabilities.

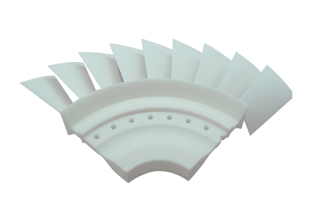

Additive manufacturing is an innovative technology that is reshaping numerous industries and research fields. Compared with traditional manufacturing, 3D printing offers several advantages, including reduced material waste, greater design freedom, low cost, rapid prototyping, suitability for small-batch production, and integrated assembly.

Epoxy resins are widely used in many devices and components, such as automotive parts, printed electronics, coatings, adhesives, and fiber-reinforced composites.

3D-printable epoxy resins have advantages over traditional materials due to their low cost and ability to form complex geometries rapidly. In the broader field of epoxy 3d printing, key technical factors include curing behavior, resin type, photoinitiators and curing agents, and the performance of the printed parts. Optimizing printing processes and material characteristics is essential for improving the commercial viability of epoxy-based materials and components produced via 3D printing.

Isotropic materials exhibit consistent properties when tested in multiple directions. This contrasts with anisotropic materials, whose properties vary with direction. Examples of isotropic materials include metals, plastics, and glass.

In materials such as epoxy resins—which typically exhibit anisotropic behavior—achieving induced isotropy is an important research direction in materials science, enabling the fabrication of components with enhanced mechanical performance and functionality.

One commonly used 3D printing process is material extrusion (MEX), also known as fused deposition modeling (FDM) or fused filament fabrication (FFF).

In MEX, epoxy filaments are relatively easy to handle because they are supplied in solid form. In contrast, powders used in selective laser sintering (SLS) and liquid photopolymers used in stereolithography (SLA) are often hazardous, require careful handling, and demand specific storage conditions. With ongoing advancements in tetra material technologies, MEX can also process a broader range of materials—including thermoplastics—than many other additive manufacturing methods.

Material extrusion is also more cost-effective than other processes and enables multimaterial printing using multiple extrusion nozzles. The extruded material can be functionalized with additives without being subject to the constraints that techniques like laser sintering impose on filler incorporation.

However, the MEX process is limited by the rapid solidification of printed material after deposition. Weak interlayer bonding results from restricted diffusion and entanglement between layers and infill lines. These limitations necessitate additional techniques to overcome mechanical anisotropy.

Several approaches have been explored to address mechanical anisotropy in MEX-printed materials.

One strategy is to optimize printing parameters—such as print speed, layer height and width, and temperature—to achieve stronger interlayer adhesion. Additionally, orienting printed components in an optimal direction can improve mechanical behavior. However, these methods must be applied individually and constrain design freedom.

Other approaches focus on optimizing material composition and manufacturing processes. Resin fillers, such as carbon nanotubes, can be incorporated into the material, followed by microwave irradiation to promote localized heating and enhance polymer chain diffusion, thereby improving interlayer adhesion.

Some studies have reported inducing crosslinking in filaments through gamma irradiation, while others have used lasers to introduce localized thermal energy to improve bonding between layers. However, these methods are often costly and require complex equipment and multiple processing steps.

Thermosetting materials offer another pathway for achieving isotropy in MEX-printed parts. A recent study reported that thermosetting polymer filaments can be extruded using low-cost MEX printers for the first time. This technique relies on a post-curing process that induces crosslinking, thereby overcoming mechanical anisotropy formed during the MEX printing process.

Researchers incorporated high-molecular-weight solid epoxy resin and added liquid epoxy resin with functional additives into the formulation, enabling multifunctional material development.

Single-walled carbon nanotubes were added to impart electrical conductivity. The authors noted that other functional fillers—such as flame-retardant or antistatic additives—could also be incorporated to meet broader application demands.

By incorporating conductive fillers, the printed components can exhibit sensing capabilities, such as piezoresistive sensing. Additionally, carbon nanotubes enable integrated temperature-sensing functionality for smart components. Concept-proof studies have already demonstrated temperature and strain sensing using MEX-printed functionalized materials.

These findings highlight future research directions, including further exploration of sensing capabilities, understanding electrical anisotropy, improving material reproducibility, and evaluating the effects of varying filler loadings. Collectively, these studies demonstrate the potential of 3D printing in developing high-performance components and enabling applications in advanced electrical and electronic systems.